by Cody Major

The Lamentation with John, Mary Magdalene, and a Witness is a fifteenth century single woodcut made by Michel of Ulm. Below the image, there is a lengthy inscription, which is interesting in itself. [1] This inscription is actually a prayer that would likely have been read while observing the image for personal devotion. The prayer derives from a fourteenth century lament that elaborates on Christ’s and Mary’s suffering during the Lamentation scene. This prayer demonstrates the interaction of image and text as devotional aids in late medieval Christianity. Text is just as important, if not more so, than image itself. The translation of the last three lines of Mary’s Lament are especially distressing:

O flowing well of eternity, how thou hast run dry. O wise teacher of humanity, how thou hast been silenced. O splendor of sunlight, eternal light, how thou hast been extinguished. O abundant wealth, how shinest thou amidst great poverty. O joyous gladness, how thy countenance is full of sorrow. O dear child, if I knew not in my soul whom thou wert, thou wouldst be a stranger to me. O dear child in my soul how thou hast been tortured and wretchedly put to death for me. [2]

The Lamentation has always been a scene that is filled with emotion, sadness, and grief; this depiction is no different. Viewers of this woodcut were intended to relate to the suffering of Mary and the death of Christ and use that emotion to focus on their own penitent devotion to God. This Lamentation scene has a grouping of four figures in the central middle ground as a lone figure observes in the right middle ground. Christ lies horizontally in the foreground; his head rests on Mary’s legs, with his mouth open and his eyes closed. His stiff, malnourished, and skeletal corpse gives an eerie sense of realism that other romanticized images of the dead Christ lack. All three of the surrounding figures have similar long, flowing drapery. The three figures also have similar despondent and mournful expressions on their faces, especially Mary. She has the most dramatic and sorrowful expression of the group, which is significant. In the middle of the image rises the wooden cross, with symbols of the Passion hanging from its arms including the nails and the whip and flail with which Christ was tortured. On the right, in the middle ground, there is an onlooker observing this poignant scene. This man may indeed be the patron of the work, or at least a model for the viewer of the image as an onlooker to the grief of the family and followers of Christ.

Many other woodcuts from this time period also use text and image to stimulate an emotional response toward a religious theme. The single sheet woodcut was an affordable, accessible object for the common population to acquire, as opposed to lavish illuminated manuscripts and Books of Hours that wealthier patrons could afford. These small devotional works combined many tangible attributes. Viewers of these woodcuts would observe and touch the religious images, read the inscriptions, possibly write additional notes in the margins, pray, and meditate.[3] People in the fifteenth century would want these intimate works to decorate their personal altars, or to carry on themselves so, they had the object to aid them in prayer.

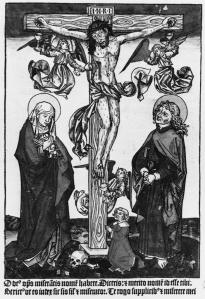

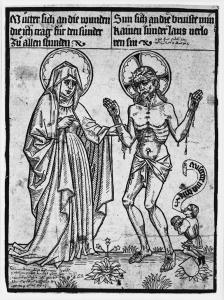

This intensely themed and vividly colored woodcut of the Lamentation is an example of what Peter Parshall, the scholar of northern Renaissance, calls “striking images,” vivid images that are intended to imprint themselves on the human brain to form equally vivid memories.[4] The “striking image” is a concept with special relevance to fifteenth century devotional woodcuts and engravings, which were small, portable, intimately personal objects that generally depicted extremely emotionally powerful or disturbing subjects, including the Crucifixion, the Lamentation, the Resurrection, and the Man of Sorrows among other themes involving intense emotion[5]. An anonymous fifteenth century Crucifixion (Fig. 1), for instance, is accompanied like the Lamentation with a text intended to deepen the reader’s thoughts about the reason for Christ’s death. An important aspect of this work in particular, is that the patron is shown, in very small scale, at the base of the cross. The patron kneels in prayer as he looks up at Christ. The inscription at the bottom of the image talks about the merit of Christ’s name, the need to pray for salvation, and mercy of Christ the judge. Another example of what might be termed a “striking” woodcut, Christ as Man of Sorrows (Fig. 2), shows Mary with the bleeding, pained figure of Christ. Here also is a depiction of the small patron kneeling beside Christ. Above Mary, an inscription reads, ” Mother, you who gaze on my wounds that I bear for all sinners for all time. ” This text calls on the viewer to realize and relate to the pain and suffering that Christ endured not only for humanity but for the viewer’s own sins. In the same vein, the text above Christ’s head asks the viewer to look on Christ’s bruises. A speech scroll issuing from the patron reads, “Mercy on me God, ” words that the actual viewer would undoubtedly have read during his devotion. A second anonymous fifteenth century Man of Sorrows (Fig. 3) depicts Christ as holding the same tools (the whip and flail) that are depicted hanging on the beams of the cross in the Lamentation woodcut. The text at on the bottom of the image reads,” This Holy figure appeared to Saint Bridget as the heart of Jesus. ” This is particularly interesting because it presents the viewer not with the image of the suffering Christ but, rather, a particular vision of the suffering Christ experienced by the Swedish saint Bridget. This woodcut may have deepened the realism and accessibility of the image of the Man of Sorrows for the devotee by authenticating the image, in some sense. The picture claims to reproduce the saint’s vision. The saint implicitly witnesses to the truth of the image.

These woodcuts were crucial to the understanding of how ordinary people actually practiced their personal devotion in late medieval Christianity. These images were made to invoke intense emotional responses in the viewer. The owners of these devotional woodcuts were supposed to see these images and contemplate and imagine the suffering of Christ and Mary. Viewers would see Mary crying about the death of Christ, the picture would trigger the viewer’s sense of empathy, just as witnessing a weeping person in life triggers our feelings of empathy and compassion. Through the picture, the devotee could share Mary’s grief along with her.

Further Readings

1. Areford, David S. The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe . Visual Culture in Early Modernity. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010.

2. Areford, David S. and Macdonald, A. A. and Ridderbos, H. N. B. and Schluseman, R. M. “The Passion Measured : A Late-Medieval Diagram of the Body of Christ.” Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1998.

3. Babcock, Roger G. and Cahn, Walter and Patterson, Lee. ” A Late Medieval Devotional Miscellany.” New Haven: The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 2001.

4. Field, Richard S. “A Popular Print for Personal Devotion,” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1997/1998):42-51.

5. Hernad, Beatrice. “Some Early German Prints in Munich Manuscripts,” Print Quarterly (1987): 45-47.

6. Karr, Suzanne. “Marginal Devotions: A Newly Acquired Veronica Woodcut,” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2002): 98-104.

7. Wolff, Martha. “An Image of Compassion: Dieric Bouts’s “Sorrowing Madonna.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies (1989): ( 112-125+174-175).

[1] For more information about woodcuts and workshops see Alison G. Stewart “Early Woodcut Workshops” Art Journal (1980): 189-194. Also see Arthur M. Hind An Introduction to A History of Woodcut: With A Detailed Survey of Work Done in the Fifteenth Century. (New York: Dover Publications, 1963).

[2] Peter Parshall, Origins of European Printmaking: Woodcuts and Their Public (Yale University Press, 2005), 236-238.

[3] Parshall, Peter. The Woodcut in Fifteenth-Century Europe. Published by the National Gallery of Art, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts / Distributed by Yale University Press, 2009.

[4] Parshall, Peter. “Art of Memory and Passion,” The Art Bulletin (1999): 456-472.

[5] Hass, Angela. “ Two Devotional Manuals by Albrecht Dürer: The “Small Passion” and the “Engraved Passion.” Iconography, Context and Spirituality,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte (2000):169-230.